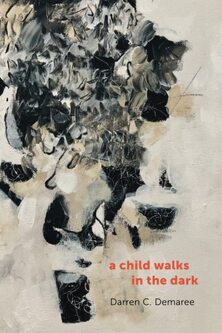

Darren C. Demaree’s new book, a child walks in the dark, reads like a dream—quite intentionally. This collection of fifty-nine prose poems, each addressed to one or more of his children, evokes a drifting sort of reflectiveness fitting to the kind of half-sleep known by many parents all too well, assessing the triumphs and challenges at the end of any given day as we prepare for what comes next.

Since each poem follows a similar structure, they develop a unified thread throughout that deepens as the reader floats from page to page. Readers who prefer more variety in full-length collections may be turned off by this style, though it worked for me. Each bracketed title mirrors the opening line after Demaree’s address to his son, daughter, or children, which then gives way to a single unpunctuated, uncapitalized stream of consciousness. As Demaree lets us overhear the affection, advice, and honesty he hopes to share with his kids, this poetic simplicity enables readers to identify with a kind of raw vulnerability perhaps only feasible in our silent moments, left to ourselves in the dark. As someone still relatively unversed in prose poems, I found this approach accessible and easy to navigate. Because of Demaree’s overarching vision for the collection, my experience as a parent could naturally follow the thread. That said, I think these poems could still easily translate for other creatives simply trying to make sense of their own legacies, confront their demons, or deal with the limitations of their daily lives, since these realities affect writers with all kinds of family or household configurations. Although a child walks in the dark focuses on the experience of parenthood, it also raises questions about how we can redeem our personal pasts and pass along the best of us to whatever kind of community will follow.

Because of Demaree’s uniform approach throughout the collection, my experience of reading it was less one of remembering individual poems than of recalling particularly elegant lines as I kept reading. For example, when instructing his daughter how to “read all the books,” Demaree writes that rather than going after every book, she should dig deeply into one and make it her own: “eventually you’ve been living the all-story and the library will feel exactly like a church.” Or in another poem, he tells her, “you are more than any pale gesture the world chooses to make.” These lines speak to me as a parent but also as a daughter, as I am reminded of the love my own parents tried to pass onto me or (more often) of things I wish I’d heard them say. Such gestures continually deepen Demaree’s poems to help reconnect us with these primal relationships—links that often hover just below consciousness but never quite leave us alone. Every affirmation of his children throughout this book could best be summed up in the closing line of one poem: “i will hold every incarnation of your world as part of my own.”

As a contribution to the literature of parenthood, Demaree’s observations are most welcome in their earnestness: while he avoids sentimentality largely through his casual poetic style, these poems also vibrate with affection for his children. They are never seen as the enemy to creativity or as an unwieldy obstacle to overcome. It is refreshing to see more writers presenting this vision of how to develop a creative career that can be large enough to contain the many other personal aspects of one’s life. Particularly in the wake of the pandemic, when most of us have had to learn how to bring the many disparate threads of our lives together under one roof, this holistic approach to creativity strikes me as all the more urgent now as we try to pick up the pieces of what remains and rebuild a more generous approach to our writing lives.

a child walks in the dark shares a name with his new podcast on parenting and creativity, a collection of interviews with other writers “explor[ing] the role of a creative person as a parent as they attempt to navigate the world their young people are growing into.” The book is Demaree’s sixteenth full-length collection of poetry, and he has several more on the way according to his website. Whatever he’s doing, it must be working. I’d like some of that magic to rub off on me in my dreams.

Since each poem follows a similar structure, they develop a unified thread throughout that deepens as the reader floats from page to page. Readers who prefer more variety in full-length collections may be turned off by this style, though it worked for me. Each bracketed title mirrors the opening line after Demaree’s address to his son, daughter, or children, which then gives way to a single unpunctuated, uncapitalized stream of consciousness. As Demaree lets us overhear the affection, advice, and honesty he hopes to share with his kids, this poetic simplicity enables readers to identify with a kind of raw vulnerability perhaps only feasible in our silent moments, left to ourselves in the dark. As someone still relatively unversed in prose poems, I found this approach accessible and easy to navigate. Because of Demaree’s overarching vision for the collection, my experience as a parent could naturally follow the thread. That said, I think these poems could still easily translate for other creatives simply trying to make sense of their own legacies, confront their demons, or deal with the limitations of their daily lives, since these realities affect writers with all kinds of family or household configurations. Although a child walks in the dark focuses on the experience of parenthood, it also raises questions about how we can redeem our personal pasts and pass along the best of us to whatever kind of community will follow.

Because of Demaree’s uniform approach throughout the collection, my experience of reading it was less one of remembering individual poems than of recalling particularly elegant lines as I kept reading. For example, when instructing his daughter how to “read all the books,” Demaree writes that rather than going after every book, she should dig deeply into one and make it her own: “eventually you’ve been living the all-story and the library will feel exactly like a church.” Or in another poem, he tells her, “you are more than any pale gesture the world chooses to make.” These lines speak to me as a parent but also as a daughter, as I am reminded of the love my own parents tried to pass onto me or (more often) of things I wish I’d heard them say. Such gestures continually deepen Demaree’s poems to help reconnect us with these primal relationships—links that often hover just below consciousness but never quite leave us alone. Every affirmation of his children throughout this book could best be summed up in the closing line of one poem: “i will hold every incarnation of your world as part of my own.”

As a contribution to the literature of parenthood, Demaree’s observations are most welcome in their earnestness: while he avoids sentimentality largely through his casual poetic style, these poems also vibrate with affection for his children. They are never seen as the enemy to creativity or as an unwieldy obstacle to overcome. It is refreshing to see more writers presenting this vision of how to develop a creative career that can be large enough to contain the many other personal aspects of one’s life. Particularly in the wake of the pandemic, when most of us have had to learn how to bring the many disparate threads of our lives together under one roof, this holistic approach to creativity strikes me as all the more urgent now as we try to pick up the pieces of what remains and rebuild a more generous approach to our writing lives.

a child walks in the dark shares a name with his new podcast on parenting and creativity, a collection of interviews with other writers “explor[ing] the role of a creative person as a parent as they attempt to navigate the world their young people are growing into.” The book is Demaree’s sixteenth full-length collection of poetry, and he has several more on the way according to his website. Whatever he’s doing, it must be working. I’d like some of that magic to rub off on me in my dreams.